Originally published in The Atlantic

In South Africa, where cellphones are as common as they are in the U.S., tech is often associated with violence and even death. Last December, a ninth-grader was stabbed repeatedly in the chest for refusing to hand over her cellphone to a robber in Durban. The year before, South Africa’s soccer captain Senzo Meyiwa was shot down by armed men in a botched attempt to steal his mobile phone in Johannesburg. But sometimes, technology is used to try and circumvent violence in the country.

“Ongoing issues of personal security affect most South Africans,” said Nancy Odendaal, an urban planner and senior lecturer at the University of Cape Town. Odendaal has interviewed immigrants in major South African cities who’ve been subjected to, as she put it, “dreadful xenophobia.” “My respondents used their cellphones to stay in touch with one another, give advice on what places to avoid, and what to wear to not stand out to foreigners,” she said.

Still, it’s mostly the non-poor who benefit from these advances, she said, pointing to apps developed by security firms and targeted at people who have money. “But, of course, those most adversely affected by violence are poorer folks living in informal settlements and townships.”

Twenty years after the Apartheid government was overthrown, more than half of the country’s 52 million people survive on about $53 a month. The government acknowledged at the end of its latest poverty-trends report that the way to address this issue is by placing a greater emphasis on battling structural issues like a lack of education, historical segregation, and areas of high crime that perpetuate inequality in South Africa. And as technology begins to become a part of South African culture, a handful of companies and nonprofits in the country are trying to harness the fledgling information-and-communications-technology industry (ICT) to take on these issues. The hope is that people heavily hit by violence and inequality can be recruited to stable jobs in a booming industry—but the results of these efforts are still in beta.

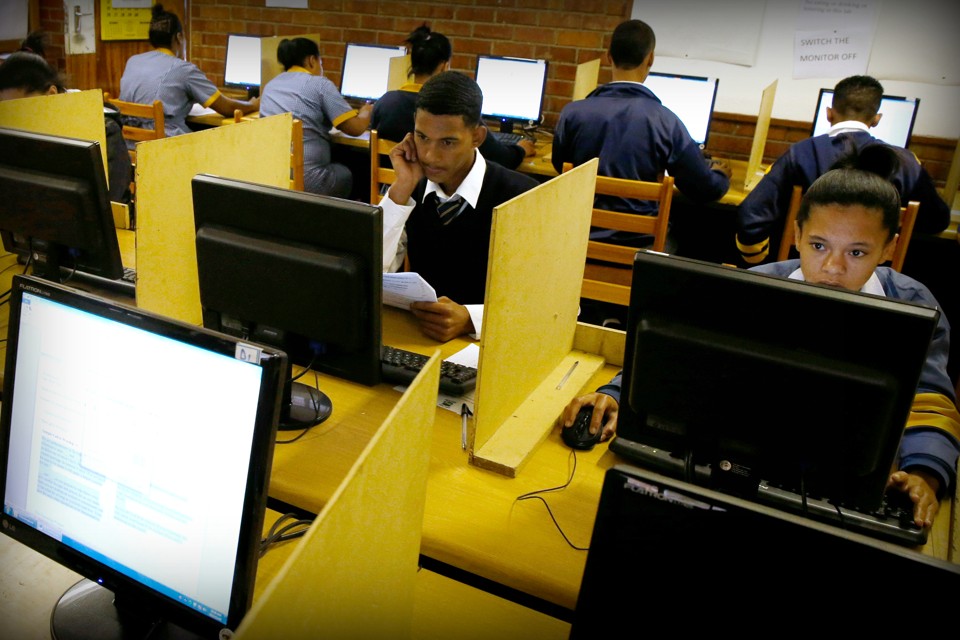

The programs aim to train people from disadvantaged backgrounds to be able to work in ICT, equipping them with skills such as computer programming, app building, and web design. The ideal outcome is two-fold: Disadvantaged South Africans can learn a coveted skill set that has the potential to energize the economy and consistently give younger generations plenty of job opportunities. However, the ICT industry has not made much of a dent in the country’s poverty thus far. So how successful are these well-intentioned tech initiatives in making lasting change? And, when students agree to participate, do they really understand what they’re signing up for?

* * *

Lungi Zungu, 28, was born in a mixed-race township in Durban, a city in the coastal province of KwaZulu-Natal.* One of a handful of people from her community to study ICT at the university level, she applied to complete a program at a tech development organization called CapaCITI after struggling to find a job post-graduation. CapaCITI works to train South Africans in software development, programming, and IT support, then connects students with companies for permanent positions. Zungu is now a full-time software developer at Sanlam.

“What we are trying to do is simultaneously address the tech skill shortage that companies face in the Western cape, as well as provide opportunities to unemployed youth,” said Alethea Hagemann, a skills-development-program lead at CapaCITI, describing her organization’s work as a “win-win situation.”

But critics of programs like CapaCITI warn that technology isn’t a fix-all for South Africa’s systemic problems, and shouldn’t be treated as such. “There’s this tendency to see technology as a magic bullet,” said Chenxing Han, a professional writer who studied the negative and nuanced sides of mobile technology in Cape Town. “There are these ideas and then there’s the reality: Running into barriers.”

A myriad of barriers stand between disadvantaged communities and the country’s flourishing tech sector. For one, although the South African government allocates more money to education than any other sector of its public spending, studies show that South Africa has “one of the worst school systems in the world,” according to World Policy. Before 1994, education in South Africawas racially organized, with separate schools, universities, and teacher colleges. Today, high-school students don’t take general technology as a subject, and students who live in historically resource-starved areas don’t necessarily developtechnological literacy from a young age. A lack of reliable electricity also makes it difficult to have working technology inside the classroom, and the Internet itself is pricey. What’s more—even if students like Zungu have a university degree, there aren’t necessarily enough companies who can employ them, in part because of a saturated tech market, budget constraints, and a lack of consumers.

Bryan Pon, the research director at Caribou Digital, a think tank that analyzes how technology is changing in emerging markets, believes that it’s overly optimistic to expect nonprofit or start-up programs to lead to sustainable economic opportunity. After all, if a large percentage of the population doesn’t have money to pay for Internet, there’s little demand for the development of products that live online. And the South African tech industry can’t provide the kind of funding, mentor networks, or institutional advantages to budding developers that are available in the West, so it’s harder for companies to get off the ground.

“When you don’t have [these advantages], especially in a resource-constrained setting, it becomes very hard to launch and scale digital businesses,” Pon said.

It’s also a matter of connectivity. Internet access in South Africa is dominated by a company called Telkom, and sent out in throttled, expensive packages to paying customers. That means that, for many township residents, Internet is a luxury that will remain out of reach.

Another barrier is that the social framework these digital businesses need to stand on remains fractured by the ghost of the Apartheid government. Apartheid forced non-white South Africans into separate living areas known as townships, and communication with white people was limited. Driving black South Africans from their homes plunged them into poverty and exacerbated income inequality. In 2016, whites and non-whites are still deeply segregated. Socioeconomic rights are included in the constitution written after the Apartheid regime fell, but the country still grapples with high rates of crime and unemployment. Many non-white South Africans still live in the townships like Zungu grew up in, and it’s rare that people leave to go to college.

Although CapaCITI has had a profound impact on her life, Zungu acknowledges that the benefits do not extend to the community—there are far more sinister components at play that keep township residents from breaking into the tech industry. “Let’s say you grew up in a township and then you’re the only one in your area who studied. Then once you have a job, and once you’ve succeeded, you just move and come to the city. We don’t always take it back [to our communities],” Zungu said. “If I were to live in a township, and then find a job, I would move to the city just to live in a better space, because of technology.”

CapaCITI also acknowledges that the program is successful on an anecdotal basis, not a structural or widespread one, and has spread largely by word-of-mouth.

“We currently have 300 people that are set to be trained this year, with a proposal to do another 3,000 within the next few years,” said Hagemann. She also acknowledges that the program does not return to the areas that are hardest hit by a lack of technological infrastructure.

“I think for us it’s about developing that consciousness, and that desire to want to reinvest after having benefitted from a great opportunity themselves.”

* * *

The tech industry is still downloading in South Africa, but initiatives to normalize ICT continue to develop at a rapid-fire pace, finding new ways to take the privilege of technology and make it more broadly accessible.

Mark Surman, the executive director of Mozilla, says that it’s important for programs like Mozilla Learning to exist to teach digital literacy—the ability to use the Internet to “find, evaluate, create, and communicate information”—to communities that don’t have it. “Most governments look at digital literacy as basic tech skills of using computers, but there is another social side of how we interact in the digital world,” Surman said. “You want digital literacy in the schools, but also need much more popular culture involved, or we will not go fast enough.”

In order for this to happen, Surman believes, children need to engage with information online. They need to understand that being able to create and communicate, whether that is putting content on a blog, or learning how to code, is just as important as interacting and consuming data. It could mean video games or social media—anything that is a big enough part of the popular culture to have an influence.

Zungu is optimistic as well, and plans to use her skills to give back to township communities.

“I feel like I am a role model,” she said. “You don’t find many young black women who are software developers. Technology is something that everybody should be exposed to. People shouldn’t only just see things on TV, and then think that things are only possible to certain people.”